An Engineer who loves living the high life

This article looks at the career path of Clayton Topkin. His career combining working at height and his love of life at sea level. From the high life of RF Surveying, to sea level as a Yachtmaster trained sailor, then back up to become a Troubleshooting Technician on Offshore windfarms.

Offshore Troubleshooting Technician on Wind Turbines

Background

Were you interested in technical things when you were a child?

As a child I would say I had a natural curiosity about the way the world worked. I recall spending hours reading random topics from a set of World Book encyclopaedias my mother purchased for the home. However, it was only at 13 when my interest in tech was sparked and flourished via computers. Consequently, it was the same year in which I transitioned from primary school to a technical high school. Here subjects like Electrical, Mechanical, Civil Technology and CAD were a part of the curriculum. When I wasn’t doing my class assignments and homework, I was tinkering with the family computer! Doing local area networks with friends on weekends. It was a good excuse to swap out hardware for an improved gaming experience. Nonetheless the saying, “Killing Two Birds with One Stone” comes to mind.

Was there a family member who was an engineer technician?

Not at all, my father worked as a postmaster for the post office in the city I grew up in (Port Elizabeth). My mother worked as a grade two teacher until the day she retired.

Mentors

Who were your mentors and inspirations as a child and when studying?

My mother’s teacher colleague had two older sons who became engineers, one electrical and the other civil. Often, she would tell me stories about which countries they had worked in. As well she would tell me about what their careers entailed and the path they took academically to achieve that. As well, the financial success they achieved. I guess that’s how my imagination was captivated. I never had the opportunity to meet either of them. However, what they achieved in their careers, I internalised. Then I used it as a beacon to inspire my own path in the engineering and technology field.

Studying engineering

Why did you decide to study electrical and electronic engineering?

It was very much a natural progression from where I left off in high school. My core elective for the last three years of my high school career was Electrical Technology which encompassed designing, building, and troubleshooting everything from three phase power circuits for motor control to electronic analogue signal analysis using oscilloscopes. By then I was dead set on pursuing a career in engineering and technology.

Ultimately, I majored in Radio Frequency and Broadcast Engineering by the time I completed my National Diploma.

Working in Electronics

What did you find interesting about a career in electronics?

The potential that exists in industrial control systems, designing a system made up of electrical hardware and components, integrating it to other systems and defining its operation via software. Then having the ability to remotely control, adjust and set its performance parameters. This ability to leverage resources and understanding of scientific principals and phenomena is immensely fascinating.

Most interesting electronics engineering job

What was your most interesting job?

Working as a Radio Frequency Surveyor. Primarily the job entailed measuring power density emitted from cellular base stations (the directional antennas which are responsible for cellular network coverage whenever you make a call or streaming data).

Within an area of say 10km2 in a densely populated city there could be more than 75 unique base transmission stations (outdoor and indoor). All with unique frequencies to avoid a phenomenon called Adjacent Channel Interference. The outdoor installations are usually mounted on high rise buildings in urban areas.

It would be my task to contact the building owner arrange access to where the antennas are installed collect its technical data, measure the building and the area around the antennas, photograph the site then draw a 3D CAD model of the installation using proprietary software developed by the company for which I was working. Simulate the power density lobes emanating from the antennas in three dimensions and from that information, designate the Occupation and Public Exclusion Zones, according the ICNIRP Guidelines (International Commission for Non-Ionizing Radio Propagation). My final task would be to draw up a technical report for the findings and make recommendations to the network operator to limit access to the exclusion zones.

It was a boat load of technical work, administrative work and traveling all at the same time. I got to see so many remote parts of my home country doing that for three years and met a bunch of interesting people too.

Working at sea

Why did you decide to work offshore?

It was around the year 2014 and it was down to a combination of career burnout and pursuing a boyhood dream of blue water sailing. I decided to move out of the apartment I was living in in Cape Town, quit my career and sell my possessions to pursue a Yachtmaster Offshore certification. With a double Atlantic Ocean crossing (Cape Town to Rio, Brazil and back) completed, many coastal miles navigated by day and night, endless charting exercises and a gruelling two-day long examination, I met my target by the third quarter of that year. Throughout my life there has always been a distinct streak of adventure and seeking out unexplored (usually physical challenges), it certainly satisfied that itch!

What did you learn from the experience?

I wouldn’t put it down to one thing.

The daily rigours of offshore sailing certainly enhanced my capacity to operate more effectively in life and in an organised environment.

For example, if I believed I was patient before undertaking the endeavour of offshore sailing, then it developed in me the capacity to exceed the level of patience I thought I was capable of at the time. If I believed I was a good communicator before, then the experience enhanced my capacity to communicate even more effectively and so on.

Offshore sailing can largely be likened to a microcosm of life. Planning and preparation, adapting to ever changing conditions, self-reflection, attaining goals etc… All of this is crammed into the size of a 42-foot sailing boat and in the timeframe, it takes to complete the journey. It’s like living life but wired up to an amplifier.

The highs are exhilarating, and the lows feel like you’ve sunken to the bottom of the Mariana Trench.

Team building and leadership

How does working offshore strengthen your team building/leading skills?

Firstly, it takes a very enterprising, independent type of person to willingly choose to operate/live in an environment where there is very little to no prospect of assistance. An environment where when things go wrong, the only pair of helping hands (other than your own) is that of your crew mates. At its essence leading is about absolute accountability. For example, if you’re delegated deck operations for the day you come to the realisation that there is a crew and captain depending on you. They are depending on you to:

trim the sails for every course steered,

keep navigational watch,

complete the logbook at every watch rotation,

helm the correct course for the passage etc.

Therefore, accepting that others rely on your effort for everyone’s wellbeing and the task at hand moulds you into becoming a better person. Which consequently garners trust in you among your crewmates.

Move to the wind industry as an offshore wind turbine technician

Why did you decide to move to the wind industry?

I achieved a lot in a short space of time in the offshore sailing industry. From achieving my licenses to working as bosun and sailing instructor at a prominent sailing school in Cape Town to working a season as deckhand in the Mediterranean on a yacht based in Valetta, Malta in 2015. I checked off a lot of boxes and ultimately, I was yearning for the stability in an organisation where I could put my engineering background to use again.

From the first-time seeing wind turbines back in 2008 in South Africa while working as radio frequency surveyor, I was deeply intrigued by these graceful industrial machines spinning effortlessly on the distant horizon. What was the magnitude and scale of erecting a whole windfarm? Who are the people that take care of them and what exactly is in the inside? These were questions which plagued my mind and I thought if I could achieve a boyhood dream of becoming a sailor then I could become a wind turbine technician.

By then in, 2015 the wind turbine market was maturing rapidly in South Africa, and I was closer than I ever was to becoming a wind turbine technician. I was adequately qualified and also experienced in working-at-heights. All I needed was some industry exposure and a few industry related certifications. I found my opportunity when I successfully landed a seven-month long apprenticeship at Saretec (South African Renewable Energy Technology Centre).

Studying again to become an offshore wind turbine technician

How was studying the second time different (compared to your earlier degree) as you had a lot of work experience to reference?

I absolutely lapped it all up and took it all in my stride. I wasted no time in learning what I was required to (and more). A good friend of mine, who now works as a Quality Manager in Wind Farm Construction for a prominent OEM in Australia, and I used to compete against each other in the examinations and lab assignments, we were very competitive. It was a wonderful time that I look back upon fondly.

Transferable skills for working on an offshore wind farm

What skills did you take with you from your engineering jobs and your marine jobs?

My strong work ethic, and my innate ability to get along with everyone.

A systematic and pragmatic approach to problem solving.

My understanding of electrical components, circuitry, and systems.

Moving countries

How quickly did you adapt to life in Sweden?

There is a saying that goes:

“It’s hard to see the picture when you’re inside the frame.”

I guess a true objective assessment about my progress should come from a native Swede.

In my defence in one year and seven months since moving here I have:

driven in blizzard conditions,

driven almost the entire length of the country in one weekend whilst moving from one county (Pitea, Norrbotten) to another (Malmö, Skåne),

had two second hand leases before moving into my own apartment, successfully completed my first Swedish tax declaration,

purchased my own car, a Volvo station wagon (a very popular car here),

achieved seven months of attending Swedish lessons (night classes),

have learnt to whip up köttbullar med potatismos (Swedish meatballs with mashed potatoes, peas, and lingonberry jam) with my eyes closed.

As well, I can:

drink my coffee black with no sugar,

navigate my way through the Uppsala Metro,

and the crème de la crème – purchase furniture from the electronic catalogue in Ikea, haul it back to my apartment and build it myself!

I’d say I am doing quite OK, hahah.

What advice would you give to someone else moving countries for work?

Figure it out based on the personality you have.

If you have a “devil-may-care” approach to life, then do that. Make the move, dive in headfirst and wing it. It’s served you well in the past and you’ll do well to manage it that way.

If you’re pedantic about planning every detail “down to a T” do your research on living costs and the logistics of the move and understand the basic laws. Either way you’ll never be fully prepared for anything you pursue.

Don’t forget to take in the best moments along the way.

Cultural differences

What are the key cultural differences you have observed?

Firstly, in companies there is very much a tendency to a horizontal organisational structure (as opposed to the traditional hierarchical ladder) and independent decision making is encouraged.

Socially I find that Swedes possess an innate respect for governance to the point where it’s part of their identity. I guess it makes one a better contributing member of society.

Lastly, no matter the weather, Swedes will always find an excuse to do an outdoor activity. Snow, rain, or sunshine being active is vital in the very literal sense of the word.

Working at heights

Can you describe the first time you worked at height?

It was circa 2008 when I began my training as a radio frequency surveyor. It was on a rooftop in the town of Stellenbosch (the winelands district in South Africa) I remember it being a clear, crisp autumn morning with the Helderberg Mountain range on one side with, the vineyards at the base of the mountain and the oak tree lined streets of the suburbs on the other side. We were utilizing a fall arrest system.

How quickly did you become confident?

Very quickly as I had undergone my Fall Arrest Training a week prior to my first real climb. In retrospect my confidence was in my training and equipment.

What advice would you give someone in their first three months of working at heights?

Apply the full extent of your training before and during every climb.

I.e., full harness checks before donning the harness, never be alone when doing a job, keep a log of weekly equipment inspections. Keep your gear clean.

When climbing always put safety first and have three points of attachment to the structure you’re climbing. In addition, never fill your hands with tools and equipment when climbing. Always utilise tool bags and attach them to your harness. Never hand over an unsecured tool while working at height, instead use a tether.

Make sure you’re scheduled for rescue simulations. Rescue simulations once, during training every two years in a controlled environment, is not enough.

Finally, enjoy the sights from above.

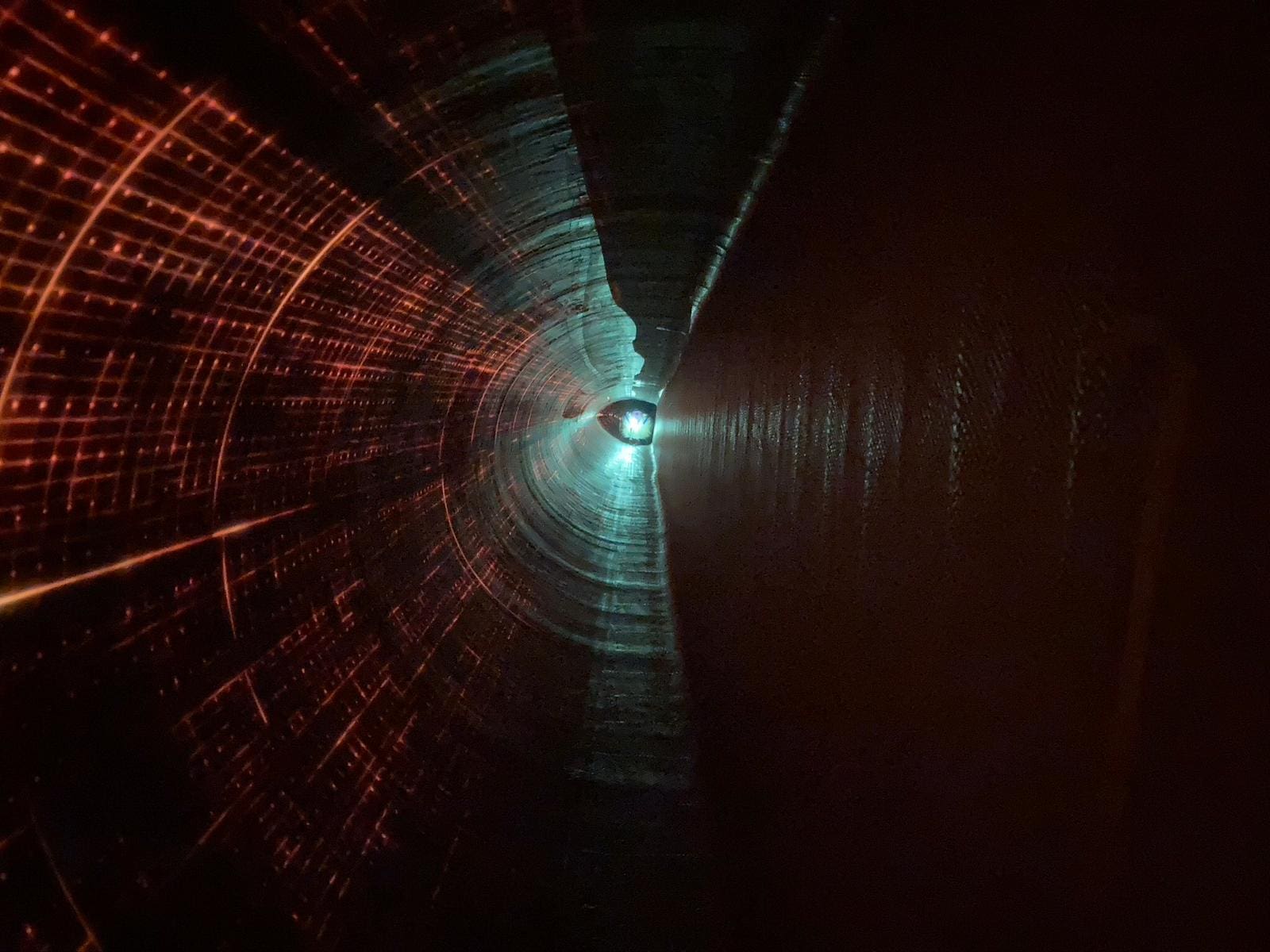

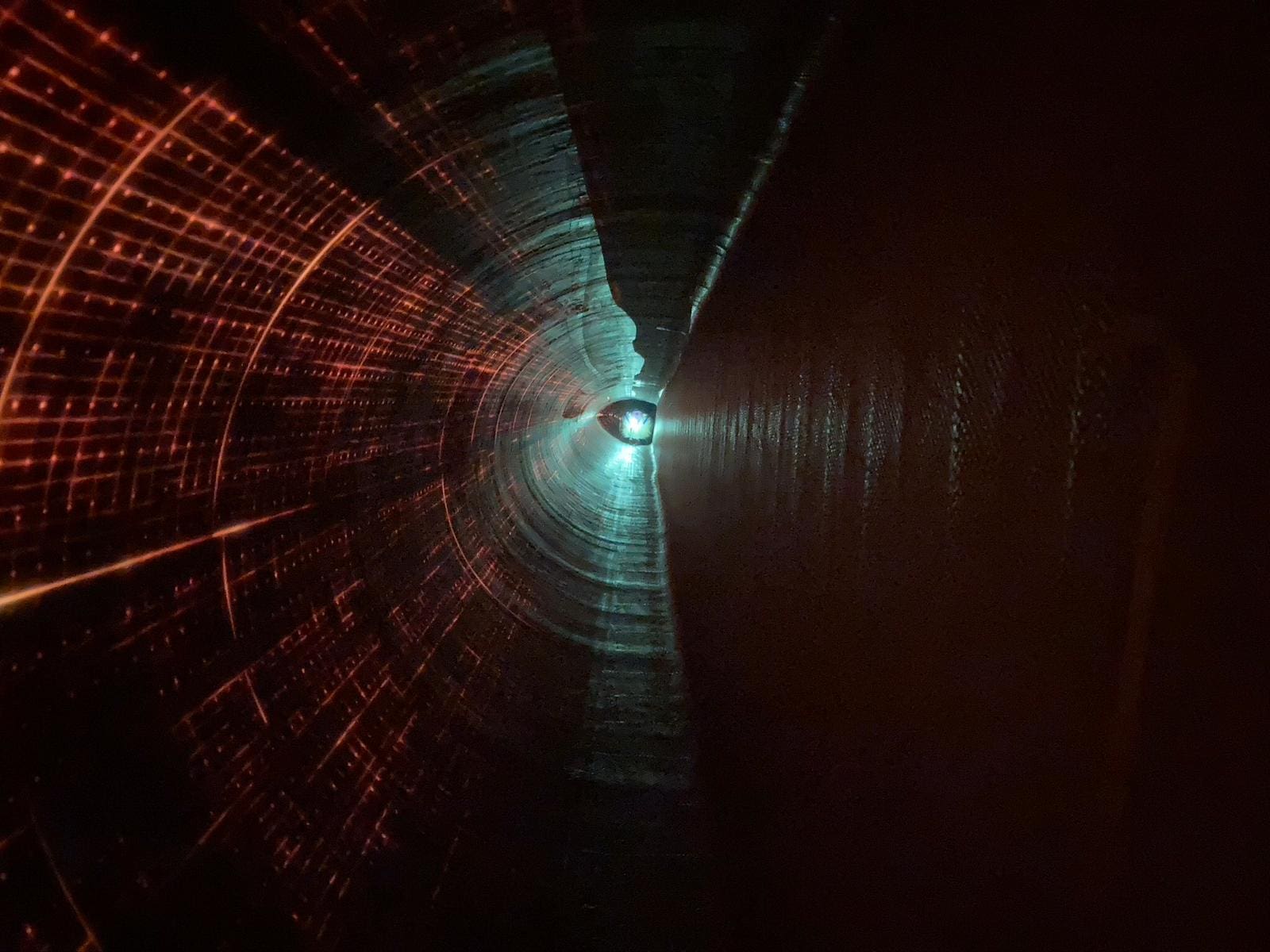

Most challenging job at height working on an offshore windfarm

What has been your most challenging job working at height?

Replacing an aviation obstruction warning lamp on the top of the nacelle while a drone was capturing footage for the Swedish TV show Högspänning. The TV series showcased Swedish electrical energy production companies, Vattenfall and Skellefteå Kraft. The aim is to give viewers deep insight as to what it’s like working on the operations end of an energy company and inspire more people to work in electrical energy production with a focus on renewable energy. Needless to say, we had a bunch of fun with the film crew for the three weeks they spent with us.

Fitness for working on an offshore wind farm

How important is your overall fitness?

It’s critical.

Every technician is expected to comfortably carry their own weight. Even though there are service lifts there is always a measure of physical climbing. Moreover, depending on the type of work you’ll be doing that day as a technician you’ll need to be able to handle and manoeuvre heavy equipment in a very confined space.

In the case of an active rescue, you may need to safely evacuate an unconscious casualty from the turbine entirely or from one part of the turbine to another. For example:

from hub to nacelle for helicopter evacuation,

or from the basement of the tower to the transition piece.

The rescuer usually undertakes this under high stress, as the casualty’s life may be dependent on the time it takes to complete the rescue. Thus, it’s important to maintain a high level of fitness and strength.

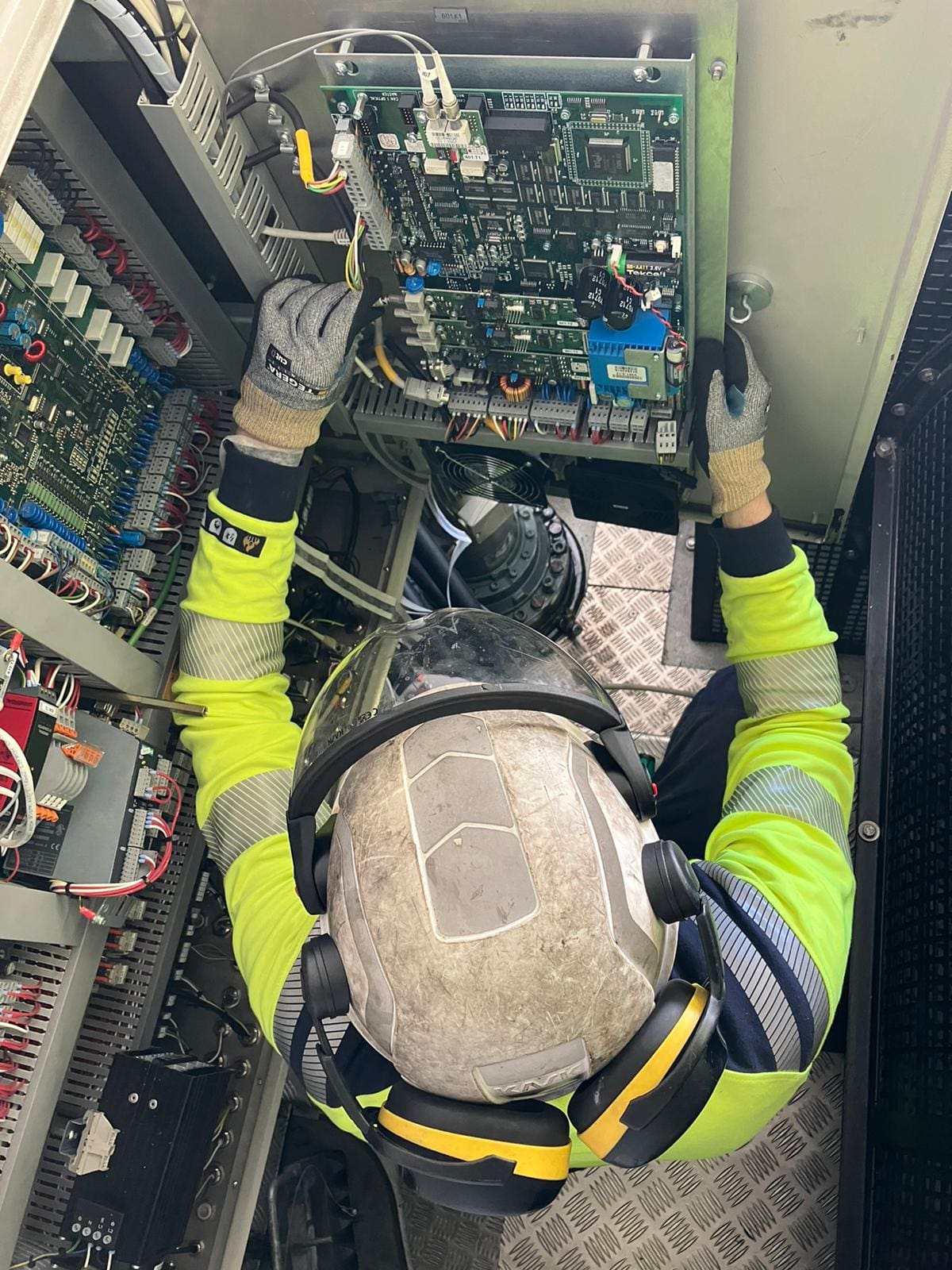

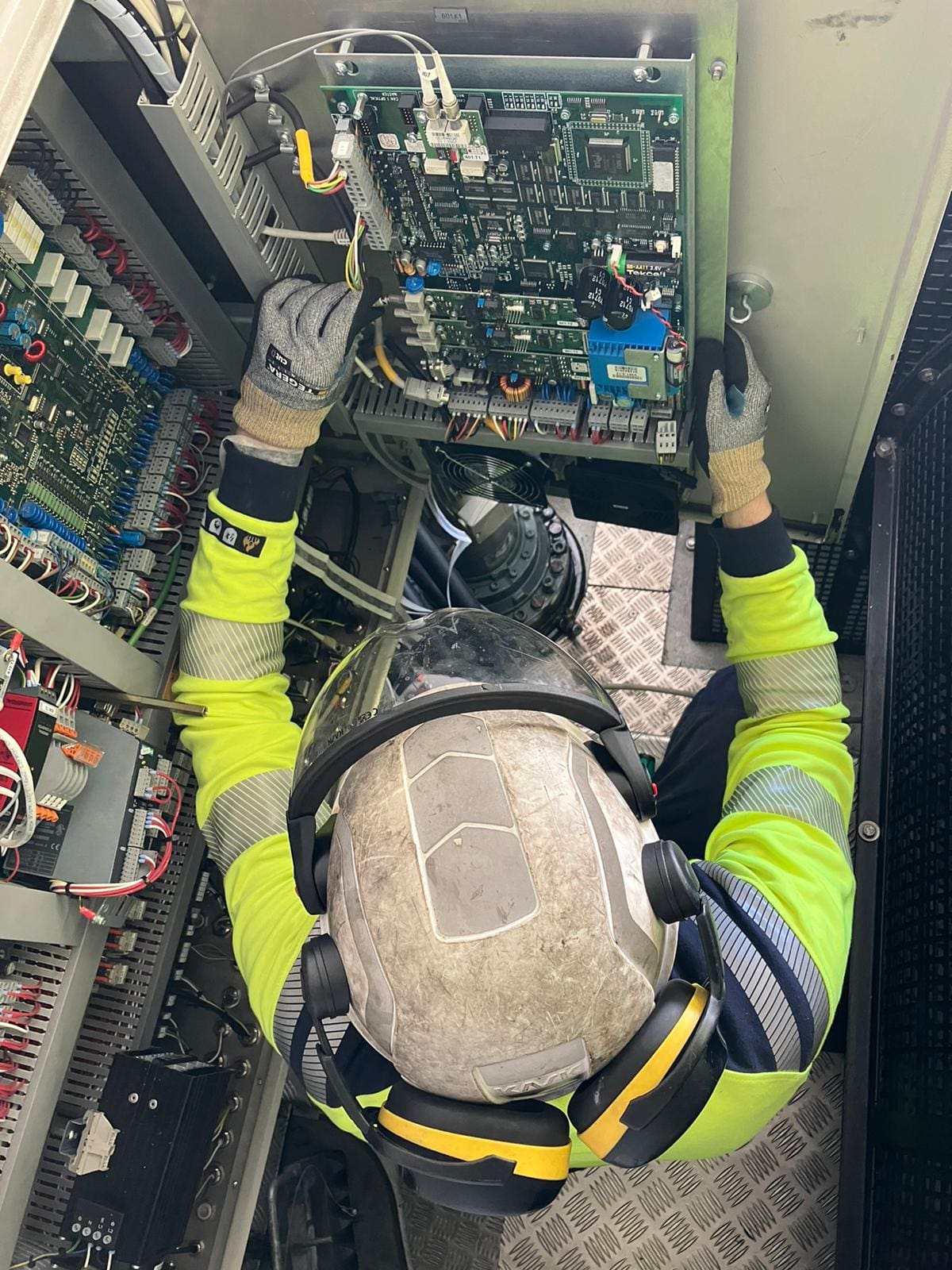

Safety clothing when working on an offshore wind farm

What sort of safety clothing, footwear and harnesses do you need to wear?

My day-to-day garments are made up of a two-piece work wear, long sleeved sweater and trousers arc rated at 9.5 calories/cm2 (Category 2) made of a blend of Modacrylic, Cotton and Antistatic textiles.

My go to pair of boots is ankle high Winter Boots. They exceed all the requirements and safety codes for the work I do inside of a turbine.

When stepping onto a turbine a climbing hat, with ear protection rated to a minimum attenuation value of 30dB, a polycarbonate eye shield with a good pair of lineman gloves is the bare minimum required to commence work.

Of course, for all climbing activities a full body harness is required.

For electrical work a pair of Class 1 rubber electrical gloves (with inner cotton liners) covered by leather gauntlets is required and disposable Nitrile gloves for handling chemicals and semi-solids like grease.

Typical week as an Offshore Troubleshooting Technician

What exactly is an Offshore Troubleshooting Technician?

To define the primary tasks, I undertake: I conduct corrective maintenance on faulted wind turbines that are installed at sea. The logistics of it is that I get work orders on a database generated by our service leader to fix turbines which are not producing power at any given time, as a secondary task I may be called upon to optimise a wind turbine that may be performing slightly off specification due to a failing component/part.

What’s your typical week like?

It entails a toolbox talk in the morning where the weather and that day’s operations will be discussed and any safety precautions to consider. Teams will be delegated tasks and there will be 30 minutes to pack the required tools and equipment needed for that day where it will be loaded onto the CTV (Crew Transfer Vessel). The service leader will notify the CTV captain of the crew for the day, and it will depart from the marina shortly after. The journey to the windfarm is approximately 30 minutes where the first team will be offloaded to their turbine were trouble shooting tasks will commence. This is a typical day which is repeated from Monday to Friday.

Job breakdown

How much of your time is spent ‘in the field’ – working on the wind turbines?

About 90% of my time is spent in the turbine and the other 5% is remote monitoring via SCADA (Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition) which allows us to monitor the condition and state of a turbine on a remote node (computer) and the remaining 5% is spent writing technical reports on our findings in a turbine.

How much of your day is spent on checking data and admin?

Up to an hour combined for technical reporting, logging hours worked and turbine condition monitoring.

How much travel do you do?

No travel outside of my own windfarm: Lillgrund.

What are the parts of the wind turbine that you work on?

From the electrical and hydraulic systems in the hub through the entire drivetrain in the nacelle and all its auxiliary systems (lubrication, temperature sensors, the hydraulic station, lifting crane and winch) to the power converter which converts the power from the generator to a DC and back to AC for grid compliance.

Coping with the cold when working on an offshore wind farm

How do you personally cope with the cold when working?

Thanks to our awesome First Mate, there’s always freshly brewed coffee on the CTV, so I make sure to grab a cup for myself upon returning from a task on a turbine. Personally, I will layer up during the winter season, under garments are vital and so are ankle high winter work boots. A head covering under the climbing helmet and a pair of winter lineman gloves usually do the trick.

Most challenging part of the job working on an offshore wind farm

What do you find most challenging about the work?

The irregular working hours, work on weekends and public holidays and constant exposure to extreme weather conditions.

What has been your most difficult job so far?

Exchanging three yaw gears which weigh approximately 210kg per unit in an extremely confined space and rerouting the wiring for the yaw system. All while being filmed for a Swedish TV Show Högspänning.

Have you ever arrived on site and found that it’s been much easier than you expected?

Multiple times, the trick I learnt is not to go in with expectations. Then only ever to systematically apply basic troubleshooting principles until the solution is found.

Becoming a wind turbine technician

What advice would you give to someone who has just started their first job as a wind turbine technician?

Pay attention, be someone of value to the team. Always seek out ways in which you can make a positive contribution. Do more listening than talking in your first year and find a niche for yourself. There are different types of wind technicians. These are Heavy Lift, Installation, Commissioning, Service Technician etc… do what appeals to you and master it.

Apart from a strong technical background, what are the three most important skills to have?

A healthy respect for safety protocols, good communication with your team and team leaders and a can-do attitude.

About the author

Clayton Topkin grew up, studied, and worked in South Africa. He is now living and working in Sweden. Clayton is a Senior Offshore Troubleshooting Technician for Vattenfall Services Nordic AB. He is working on an offshore wind farm – Lillgrund Wind Farm.

He also has experience with GE Renewable Energy, Siemens Gamesa Renewable Energy and Suzlon Wind Energy Corporation (SWECO).

Careers – working on an offshore wind farm

Further reading about working on wind turbines and offshore wind farms

Other wind turbine articles and stories

Responses